- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Purification of the Higher Education System and Jihad of Knowledge in Iran

GIGA Focus Middle East

Purification of the Higher Education System and Jihad of Knowledge in Iran

Number 3 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-3611

For decades, the Iranian government has pursued strategies to ideologically “purify” higher education. To this end, academic staff and students have been purged or expelled for expressing dissent, and academic content has undergone revisions. This paper reviews how purification strategies in higher education have formed over time and describes how they serve the government’s agenda at home and abroad.

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Iranian government has been adopting strategies to purify the higher education system. The founder of the Islamic Revolutionary government, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and current supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei have played significant roles in shaping and applying purification processes.

The government has perpetually been revising university curricula across all disciplines, especially in the humanities and social sciences, to ensure compliance with the state’s political ideology. This has been combined with a heavy-handed purge of university staff and students for lack of ideological and political loyalty. Strategies of purification are intensified after every round of popular uprising.

Purification of the higher education system complements Iran’s strategy of “jihad of knowledge,” which frames the state’s focus on developing forms of knowledge, which can be used to safeguard the longevity of the Islamic Revolutionary government at home and abroad.

Iran’s military, nuclear, and cyber-based advancements in recent years demonstrate that purification strategies – aimed at training loyal, talented Iranians who are willing to advance the government’s scientific projects – combined with strategies inspired by the idea of jihad of knowledge, serve the state agenda well.

Policy Implications

Iran has increased cyber-based and military collaboration with like-minded states and groups. The country’s strategies of both purification and jihad of knowledge have contributed to Iran remaining a threat to global security. Iran’s nuclear programme, built using the same set of strategies, only adds to the existing threats posed by Iran. Therefore, a global effort is necessary to stop Iran from obtaining military nuclear capability.

A Systematic Implementation of Ideology

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the Iranian government has pursued multiple initiatives aimed at an ideological reconstruction of society. A systematic approach has been implemented to infuse the political ideology of the state into every aspect of Iran’s national institutions, including academia. This systemic approach has been pursued through two streams of policies: First, the government has used various methods to preclude and expunge political dissent in the Iranian academic community, including heavy-handed vetting, expulsion, suspension, detention, and prosecution of students and academic staff for expressing contrary political views. (Such purges tend to see an uptick in the aftermath of mass uprisings in Iran.) Second, it has altered academic curricula and teaching materials and created a culture that facilitates the ideological indoctrination of Iranian students. This analysis seeks to a) explore the Iranian government’s strategies of forcing ideological frameworks onto the higher education system and b) assess the consequences of such strategies.

Through various monitoring and surveillance methods, the government measures the level of political dissent within the Iranian academic community. Generational ideological shifts, technological advancement, and the deterioration of social and economic environments in Iran have led to a visible loss of support for the state within the universities in recent years. This has been demonstrated by various cycles of popular uprisings, in which the university campuses have consistently played a key role. Consequently, the government has taken active measures to control the academic community (both students and staff) and to suppress the forces that challenge the legitimacy of the state. Alongside the purging, the government also uses vetting and quota systems to ease the entrance of loyal personalities into universities as students and staff. As such, through the unceasing suppression of dissidents and the simultaneous cultivation and promotion of ideologically compliant and politically loyal segments of the student body, the government succeeded in forming a support base across the higher education sector. Educators and teaching material also undergo constant monitoring and revision by the government. In recent years, the term “purification” has frequently been used by various senior officials in Iran, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to describe these mechanisms.

After providing a historical review of “purification” in the Iranian higher education sector since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, including the ways in which Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei have shaped this idea, we discuss the government’s strategies of purging staff and students and of altering curricula and teaching materials. Finally, we examine the consequences of these strategies in the context of the “jihad of knowledge” in terms of Iran’s power position on the global stage.

History of Purification in Iranian Higher Education

From the early days of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the country’s political leaders have always considered ideological transformation of the higher education sector in Iran as a crucial strategy to maintain the longevity of the Islamic Republic. Khomeini likened the threat posed to the Revolution by universities to that of a cluster bomb. Against that backdrop, one of the earliest initiatives of the Revolutionary government in post-1979 Iran was pursuing the Cultural Revolution (Enqelābe Farhangy). This period, which began by shuttering the universities for a two-year period during which a thorough review was conducted, was characterised by purging universities of Western-oriented ideologues and the supporters of the previous regime. The Cultural Revolution Headquarters, later renamed the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (Shuraī āli Enqelāb Farhangy), was established as the key organisation in charge of the purification process of the higher education system in Iran. The aims of the process were to replace anti-Revolutionary elements with loyal, revolutionary forces and to revise educational curricula.

In 1981 Khamenei was appointed as the head of the council. As such, the process of purifying Iranian universities became an important issue to him personally. To date, he continues to dominate the government’s policies in Iranian universities through the Office of the Supreme Leader’s Representatives. This office was founded by his decree to institutionalise Islamic and revolutionary values at the administrative and academic levels of the universities.

Khamenei’s world views, which inspire his vision for the future of Iran, have greatly influenced policies that have been adopted across the country’s higher education sector. His perception of the significant role of academic institutions in the stability of the Islamic Republic has motivated continued efforts towards such transformation. He perceives the universities as subversive bases potentially capable of overthrowing the government. Such a perspective is undoubtedly influenced by the experience of the 1979 Revolution and the role of the Iranian student movements in toppling the last Iranian monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah. Khamenei frequently refers to universities as the epicentre of the Revolution, viewing them as a hospitable environment for demanding change, with the students and academics as protagonists of that change.

Khamenei’s promotion to supreme leader, which coincided with Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s ascension to the presidency, undoubtedly provided him with an exceptional level of clout in the political landscape of Iran. His position has allowed him to expand strategies aimed at fulfilling his vision for purification of Iranian universities. During Rafsanjani’s presidency (1989–1997), the primary focus of the government was post-war reconstruction and development. This period highlighted the country’s need to expand the capacity of the universities to train more forces and rebuild the country. To this end, Rafsanjani established Islamic Azad University, the first private university founded after the Revolution. After Rafsanjani, the so-called reform movement became popular in Iran and led to the landslide victory of former president Muhammad Khatami. Khatami’s tenure coincided with the first major post-Revolution student uprising in Iran, in July 1999. Student sit-ins as a reaction to the closure of the reformist newspapers were crushed by the security forces and by the Basij militia at Tehran University. Several students were killed and many more were injured in the violent attacks by the government forces. Several students were arrested and prosecuted. Those incidents are considered as the initial phase of the student movement post-Revolution, which continues today. The experience of 1999 highlighted the potential challenge posed by the universities to the Islamic Republic.

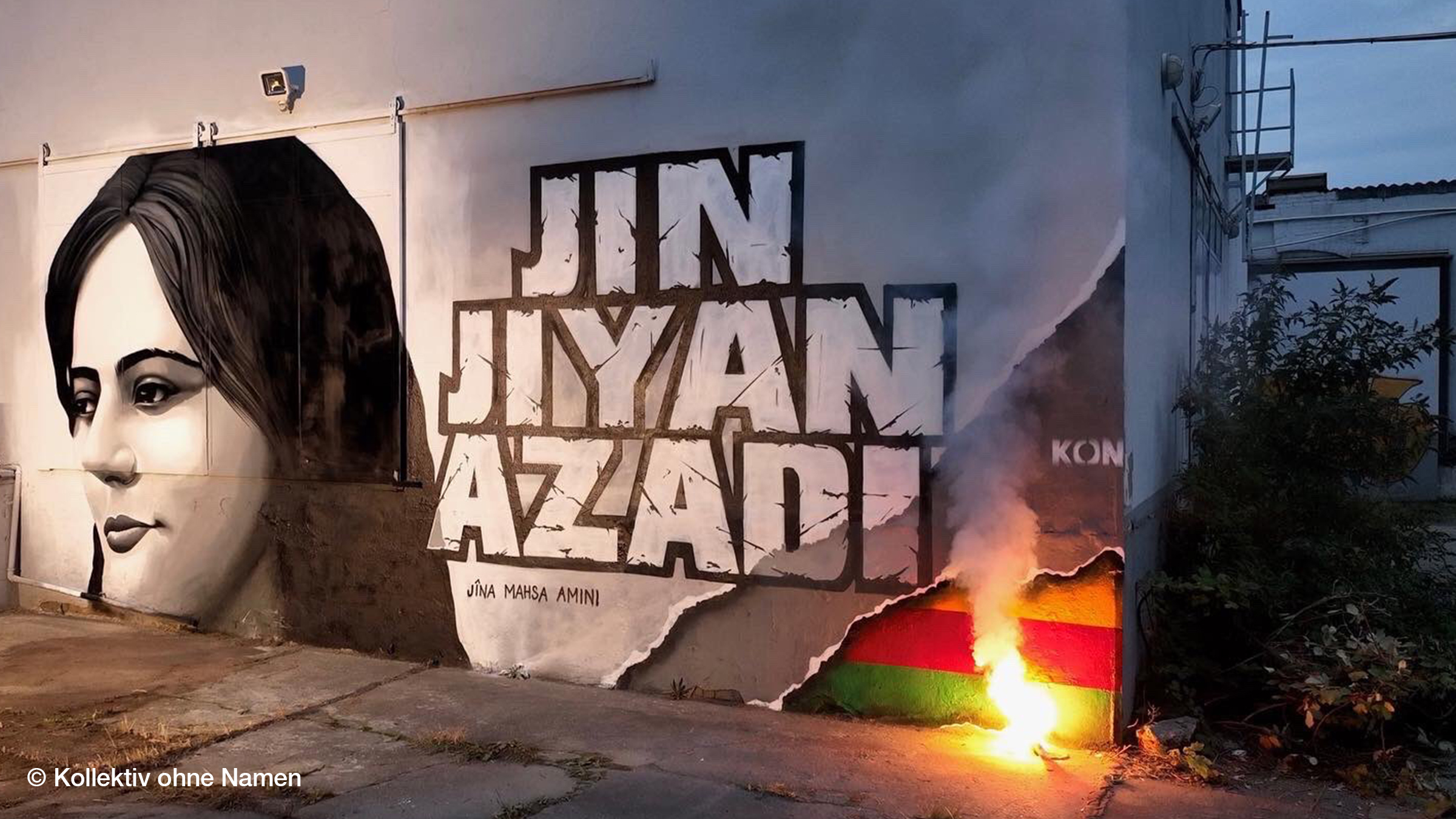

Since then, Iranian students have continued to play a significant role in protest movements. University students across the country actively participated in the post-election protests in 2009, the uprisings of December 2017, January 2018, and November 2019, and the Woman Life Freedom Uprising in 2022. Recognising the role of students in all these movements, the government has frequently taken measures to suppress dissidents and to cultivate support via loyal forces within higher education organisations. Such measures have two main components that will be analysed in the following sections: purging dissidents and revising content.

Purging Political Dissent at Higher Education Institutions in Iran

As noted, one of the most influential controlling organs vis-à-vis university campuses in Iran is the Office of the Supreme Leader’s Representatives, which operates in every university. It is directly managed by the Office of the Supreme Leader and is enmeshed in all the institutional decision-making processes of the respective universities. The realm of influence of the Supreme Leader’s representatives extends to various areas including overseeing the adherence to Islamic and Revolutionary values in the administrative, cultural, political, social, and sports activities of university campuses. They also play an important role in organising religious and political events, as well as mobilising the student Basij body.

Since 1979 the government has compiled and implemented a strict disciplinary code of conduct including regarding the acceptable personal attire of students on university campuses nationwide. This detailed code includes a strict ban on the use of perfume, makeup, and colourful clothing. Upon initial registration, students are required to sign a pledge that they will adhere to these guidelines (Iran International 2023). Such a code of conduct, emblematic of the government’s efforts to assert its ideological influence within educational institutions, reflects its broader strategy of aligning the university environment with its political, ideological, and cultural objectives.

Khamenei regularly hosts groups of students at his residence. Attendees of these gatherings are handpicked to project an image of unwavering student support for the Islamic Republic, and for Khamenei personally. The visits are widely covered by the state-owned media in Iran to emphasise the popularity of the supreme leader. In these meetings, some students can express their opinions, which, of course, are vetted in advance by the Office of the Supreme Leader. The attendees are selected from a pool of ideologically loyal individuals, such as members of the Islamic Student Associations and the Basij Student Organisations. This reflects the importance for Khamenei of maintaining a direct link with university students. It also indicates efforts to portray Khamenei as a popular leader amongst young and educated Iranians. Basij forces have become increasingly powerful in Iran, and being a member of the Basij defines an identity for the students and academic staff that outweighs their academic merit and facilitates their professional development.

Despite the pursuit of various strategies and institutional implementation of political ideology of the state in universities, widespread discontent persists among both students and staff. Such discontent has been demonstrated in student sit-ins, strikes, cancelled lectures, and other forms of protest against the imposition of ideological agendas and restrictions on academic freedom. University students, by rejecting the political Islamic ideology propagated in universities, strive to safeguard their autonomy in political, social, and academic spheres. In response, the government continuously purges students for expressing their opposition to such strategies through multiple cases of expulsion, suspension, eviction from dormitories, and “academic exile” (transferring students against their will to universities far away from their hometowns). Vetting mechanisms that are administered by various government ministries and official bodies including the National Organisation of Educational Testing (Sazman Sanjesh) oversee constant monitoring of and reporting on the students. Their primary objectives encompass ensuring the unwavering loyalty of students to the supreme leader (through acceptance of Velayat-e Faghih), weeding out those with a history of support for political opposition groups, and confirming adherence to Islam (or one of the other three religions recognised by the Iranian Constitution: Christianity, Judaism, or Zoroastrianism). Religious affiliation with a recognised group is a mandatory pre-requisite for university admission and is used to bar, among others, members of the Baháʼí faith from university.

Two thousand cases of student rights violations were reported in Iran between 2009 and 2011, including 634 student expulsions and 400 suspensions spanning from one to several academic terms, and there were also 132 teaching staff expulsions. In the latest round of protests in 2022, the violent crackdown against university student protesters was intensified. One hundred and twenty-six cases of academic rights violations were documented in 2022. Students received harsh punishments, including suspension from continuing their education, long prison sentences, and lashes. In 2023 another 416 cases of academic rights violations were reported, and 217 individuals had their studies suspended (Human Rights Activists 2024).

In addition to the above outlined measures of expulsion, suspension, and prosecution, the government has embarked on a decades-long campaign to fortify its student base within universities. This campaign has consisted of allocating admissions quotas to the families of “martyrs” (those who lost their lives in the Iran–Iraq War) and to veterans, former prisoners of war, and their families. In recent years, additional admissions quotas have been introduced for foreign nationals from countries deemed by the Islamic Republic as belonging to the so-called “Axis of Resistance.” Members of the Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Forces (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) have been given access to Iranian universities. Through these measures, the regime seeks to bolster its student constituency within universities and tip the balance in its favour. Approximately 8 per cent of students currently enrolled in public universities are enrolled through this admissions quota (Deutsche Welle Persian 2023).

In Khamenei’s discourse, enemies of the Islamic Republic are in a “soft war” with Iran and constantly seeking to ideologically conquer the country’s universities. He refers to students as the soldiers whose potential he seeks to harness to consolidate the state’s authority. He frequently emphasises the pivotal role of students and academics in preserving the Revolution’s values. In 2016 he stated in a meeting with university professors,

My advice to revolutionary students and professors is that they should play their role. We have said to the youth that they are the officers of the soft war. You university professors, too, are the commanders of this soft war. (Khamenei 2016)

In addition, the government has adopted similar measures to control and suppress dissent among academic staff at Iranian universities. Efforts to purge academics for expressing dissent have intensified over the past several years. More recently, several university professors have been either expelled, forcibly retired, or subject to temporary or permanent teaching bans.Farshid Nowruzi, vice dean of the Faculty of Foreign Languages at the University of Mazandaran, spoke up recently about his dismissal in the aftermath of 2022 uprising. He was fired, without notice, after declining the security forces’ request that he provide them with the names of students who participated in protests (Lipin 2024).

At the same time, several well-known religious ceremony leaders, known to have close ties to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and the Office of the Supreme Leader have been appointed to teaching positions at the nationally high-ranked universities. Their ideological loyalty has outweighed their lack of academic credentials (Center for Human Rights in Iran 2023).

Khamenei expressly requested the removal of academics who do not pledge full loyalty to the state from universities, saying in 2016,

Untrustworthy individuals should not be allowed to show their presence in universities. Untrustworthy individuals are those who challenge the system with any excuse. Which country allows its ruling system to be challenged by others? (Khamenei 2016)

All in all, evidence suggests that since the early days of the Islamic Revolution, the Iranian government has adopted a series of complex and well-structured measures to purge students and academics for expressing their political and ideological views. Such measures have been escalated in response to various rounds of popular uprising. The supreme leader has played a pivotal role in the formation and implementation of these strategies. His perception of the role of universities in what he perceives as a “soft war” whose aim is to change the country’s political system has been the foundation of his vision for higher education in Iran. The next section will review the government-led content revision and cultural projects carried out over the years by the Islamic Republic in an attempt to control academic institutions in Iran.

Reshuffling Content, and Re-Instating the Revolutionary Culture

This section delves into content-oriented transformations evident in university courses, educational materials, and the introduction of new academic disciplines. The redefinition of the concept of knowledge stands as a central objective of the Islamic Republic within its academic institutions. Since 1979 pushing the country’s educational system to adhere to the government’s preferred political ideology has been one of the main strategies of the Iranian government. It was introduced in the early days of the Revolution, in the form of the so-called Cultural Revolution. The restructuring of the educational system involved an extensive review of curricula in all fields. In March 1980, with a direct order from the founder of the Revolution, Khomeini, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution was founded. In his order, Khomeini delegated several tasks to the Council, including “purging the scholars and students with Liberal and Marxist ideologic affiliations,” and “turning the universities into institutions with hospitable environments to study Islamic sciences” (Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution 2013). The latter prompted a thorough review of curricula at all academic levels, a process that has been taking place ever since.

Over the years, several official government guidelines have been developed that set a structural framework for knowledge and education according to the vision and political ideology of the Iranian government. The Comprehensive Scientific Mapcompiled by the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution in 2010 and approved by the supreme leader outlines the government’s strategies to facilitate the process of compliance with state-defined Islamic values in education and research institutions. Several other entities work in parallel, operating under the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, to keep learning materials at Iranian universities under constant review, including the Organisation for Researching and Composing University Textbooks in the Humanities, and the Council for Transformation and Development of the Humanities (Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution 2007).

One of the key initiatives that began during the Cultural Revolution in Iran was the incorporation of various courses on general knowledge (doroos omoomi) into all academic programmes. The primary emphasis of these courses has been to teach the political ideology of the Islamic Revolution. Courses include “Root Causes of the Iranian Islamic Revolution,” “Political Thought of Imam Khomeini,” “Imam Khomeini’s Last Will and Testament,” and “Islamic Studies.” These modules are compulsory across all undergraduate degrees at Iranian universities. The undergraduate level in Iranian universities requires that students obtain between 130 and 160 module credits, of which 24 credits are spread across the general knowledge courses. These courses are predominantly taught by clerics approved by the Office of the Supreme Leader’s Representatives at the respective universities (Ministry of Science Research and Technology 2017).

Transformation of the teaching material has been all-encompassing across all disciplines. Nevertheless, humanities and social sciences have been subject to heavier reviews and changes by the government. In 2011 the government introduced a new initiative to revise the curriculum for 38 academic programmes in the humanities and social sciences to promote what was described by policymakers as an effort “to promote Islamic and Iranian values” in higher education. In 2019 a curricular revision of the political science undergraduate degrees across the Iranian universities was also conducted that involved launching 22 new modules. The new modules are designed to promote a certain ideological narrative and are detached from the standard political science foundation modules that are taught at the undergraduate level in most universities around the world. The new modules include titles such as: “Islamic Ethics,” “Islamic History,” “Interpretation of the Quran,” “Diplomacy in Islam,” and a module dedicated to studying Zionism and the Palestinian issue (Deutsche Welle Persian 2019).

Incorporating the government’s political ideology into the Iranian education system has not been limited to changes in modules and teaching material. The government has also founded several universities and research institutions that, unlike the existing institutions, are not overseen by the Ministry of Science Research and Technology. Higher education institutions such as Imam Sadegh University and Imam Hussain University, both affiliated with the IRGC, and Imam Baqir University, affiliated with the Ministry of Intelligence, are used as key organisations to promote more radical political and ideological orientations. Combined with the heavy-handed vetting systems, such organisations are vital in training the most loyal forces to serve in various government bodies across the Iranian political establishment. These institutions are designed to deepen the government’s influence over the education system, and their long-term goal is to train future generations of Iranians that are loyal to the political system and determined to preserve the Islamic Revolutionary government.

Over the years, various religious and political ceremonies have been introduced and organised by the Office of the Supreme Leader’s Representatives that are conducted across university campuses in Iran and aim to re-instate Revolutionary culture in academic institutions. For example, war memorial visits (rahiane noor) comprised of student trips to the southern parts of Iran, formerly the front line of the Iran–Iraq War (referred to as the Sacred Defence), have become a regular part of student cultural activities. The main aim of such activities is glorification of the war culture, in line with the Revolutionary ideological mindset of the state in Iran. In addition, Shiʿa religious ceremonies that glorify war and martyrdom, such as the mourning of the third Shiʿa imam, are held at universities to emphasise the ideals of jihad and self-sacrifice for preserving the Islamic Republic among students. In past years, the government has arranged transfer and burial of the remains of several unknown soldiers (shahide gomnam) who died in the Iran–Iraq War at various university campuses nationwide (Esfandiari 2006).

Curricular revision and constant adjustment of teaching material, along with the introduction of particular cultural activities, aim to engender an alignment of academic discourse with the government’s ideological framework, forestall an alternative narrative that may lead to political dissident, and promote compliance with the government’s political ideology. Constant modification of the education system, including establishment of new entities, serves the government’s ideological domination and advances its agenda of indoctrinating young Iranians.

The Purification Strategy’s Consequences

The emigration of talented young Iranians has been one of the main outcomes of the government’s heavy-handed ideology-driven reforms in the education system. Though it must be said that poor economic conditions and lack of future prospects have also played an important role in Iran’s brain drain. Iranian students have been increasingly seeking to secure educational opportunities abroad. Iran’s Migration Observatory reported that in 2020 alone more than 66,000 Iranian students were residing abroad. Most Iranian graduates from foreign universities seek employment abroad to obtain legal residency and citizenship in other countries. Evidence from surveys by the Migration Observatory regarding the willingness and decision to return among Iranians living abroad in the summer of 2022 indicates that about 70 per cent of Iranians living abroad, most of whom have university degrees, had “little” or “very little” desire to return (Iran Migration Observatory 2022).

As noted, one of the objectives of education reform strategies in Iran has been to dismantle any narrative that challenges the government’s political ideology. Against that backdrop, measures have been taken across the Iranian higher education organisations to undermine any form of political and civic activism. At the same time, extensive support has been provided to the students and professors affiliated with pro-government activism organs, such as the Basij and the Islamic Student Associations. The ideological domination of the government that has sought to create a monolithic political atmosphere across Iranian university campuses has also significantly contributed to the brain drain in Iran.

Moreover, lack of meritocracy in government employment, caused by heavy-handed vetting mechanisms for both students and employees that handpick individuals based on their ideological loyalty to the government has also influenced young Iranians’ decisions to leave. Iranian university graduates faced with pervasive systematic discrimination on the job market become increasingly cynical about their future. Scientific recession could be regarded as a potential outcome of the deterrence of students from continuing their education and their subsequent withdrawal from academic endeavours.

The emergence of a generation of so-called “young jihadi managers” that are trained by the ideology-dominated higher education institutions of Iran has shifted the country’s political landscape. President Ebrahim Raisi’s cabinet and the new members of parliament elected in March 2024 are strong indicators of the dominance of the young jihadi figures in the Iranian political system. The number of senior government appointments from among Imam Sadegh and Imam Hussein University graduates has risen. Trained in these institutes, such appointments are designed to maintain the ideological dominance of the government that perpetuates the orthodoxy of post-Revolutionary Iran and the longevity of the government.

The ongoing economic, social, and political challenges in Iran have led to various rounds of popular uprising over the past several years. The ongoing tension between the state and the citizens indicates that the strategies and policy choices made by the new generation of Iranian politicians have not appeased citizens. Efforts to create an ideal society by educating Iranians at institutions in line with the political ideology have failed to eradicate the risk of dissidence across Iranian university campuses. Khamenei’s concept of “purifying” higher education, meant to legitimise his power and maximise his influence by controlling future generations of decision makers through strong vetting and ideological indoctrination in universities has been challenged by mass protests of young Iranians in recent years.

The case of scientific collaboration with Western academic entities that led to the development of suicide drones by Iran (Rose and Pope 2023) is an important example of how the Islamic Republic seeks to advance its strategies of jihad of knowledge. Iran’s cyber-based, military, and nuclear capabilities have significantly increased in recent years. Such capabilities are indeed in line with Khamenei’s plan to project power and establish the IRI as a global player with a significant impact. He has openly stated that “pursuit of knowledge is a form of jihad” and that “advancement of knowledge is the secret to political and military power” (ISNA 2023).

Iran-made suicide drones and missiles being used in the war in Ukraine, and by militia groups such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen, has highlighted another dimension of Iran’s jihad of knowledge – that is, its efforts to share capabilities with like-minded states and groups. The collaboration between Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran can provide these countries with a significant quantitative industrial-military edge that contests the traditional technological superiority of Western countries.

In conclusion, the intensified purification strategy underscores the Iranian government’s structural and long-term planning in line with Khamenei’s vision. Such efforts aim to consolidate power, suppress dissent, and indoctrinate future generations of Iranians. Analysing these processes reveals that advancement of knowledge through higher education is ultimately directed towards achieving two goals: first, to maintain the longevity of the political system and, second, to facilitate the Islamic Republic’s aspiration to project power at the global level. Iran’s political leaders’ vision of a so-called “new world order” assumes that the declining power of the United States is opening space for middle powers such as Iran to project and aspire to have more influence in the global system. A key strategy in fulfilling such a vision is, according to Supreme Leader Khamenei, the pursuit of jihad of knowledge. It requires training talented ideologically loyal Iranians and collaborating with like-minded states and groups. Various rounds of student uprisings and Iran’s brain drain indicate that the government has yet to achieve full control over the higher education sector in Iran. Despite that, the government has managed to project power at the global level through nuclear, cyber-based, and military advancements. In other words, the evidence indicates that while purification strategies have not led to the expected outcome domestically, they have assisted the Iranian government in projecting power internationally through its support for destabilising and destructive activities. Against that backdrop, the West must impose more efficient controls on the transfer of advanced technologies to Iran and stop the government from obtaining nuclear military power.

Note

This Focus was created in collaboration with a co-author who wishes to remain anonymous.

Footnotes

References

Center for Human Rights in Iran (2023), Iranian Government Replaces University Professors Accused of Backing “Woman, Life, Freedom’ Protests with Regime Loyalists, 13 September, accessed 7 March 2024.

Deutsche Welle Persian (2023), رئیس دانشگاه تهران از پذیرش نیروهای حشدالشعبی دفاع کرد. [The President of the University of Tehran Defended the Admission of Hashd al-Shaabi Forces], accessed 6 March 2024.

Deutsche Welle Persian (2019), رشته علوم سیاسی یا شاخه حوزه علمیه قم در دانشگاه تهران؟[Political Science, or a Branch of Hawza at Tehran University?], accessed 12 March 2024.

Esfandiari, Golnaz (2006), Iran: Students Protest Burials Of War Dead On Tehran Campuses, 15 March, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, accessed 7 March 2024.

Human Rights Activists (2024), Annual Statistical Report of Human Rights Conditions in Iran 2023, accessed 13 March 2024.

Iran International (2023), University In Tehran Joins Strict Dress Code Regulations, 28 September, accessed 12 March 2024.

Iran Migration Observatory (2022), سالنامه مهاحرتی ایران 1401 [Iran Migration Outlook – 2022], accessed 12 March 2024.

ISNA (Iranian Student News Agency) (2023), علم و پژوهش در آینه کلام مقام معظم رهبری [Knowledge and Scientific Research in Supreme Leader’s Speeches], accessed 14 March 2024.

Khamenei (2016), فیشهای اساتید دانشگاه [Collection of Speeches Addressed to University Lecturers], accessed 7 March 2024.

Lipin, Michael (2024), Why US is Emphasizing Need to Interdict Iranʼs Weapon Supplies to Yemenʼs Houthis, Flashpoint Iran, Voice of America, accessed 14 March 2024.

Ministry of Science Research and Technology (2017), سرفصل دروس کارشناسی علوم سیاسی [Political Science Undergraduate Curriculum], accessed 13 March 2024.

Rose, David, and Felix Pope (2023), Iran’s ‘Suicide Drones’ are Being Developed at British Universities, in: The Jewish Chronicle, 8 June, accessed 10 October 2023.

Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (2013), اساس نامه دانشگاه آزاد اسلامی [Article Association of Islamic University], accessed 7 March 2024.

Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (2007), معرفي شورا [About Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution], accessed 7 March 2024.

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Sara Bazoobandi (2024), Purification of the Higher Education System and Jihad of Knowledge in Iran, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfme-24032

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.